The story begins in the 19th century with the search for the fabled Northwest Passage, a sea route through the Arctic between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. A particular expedition led by Sir John Franklin in 1845 that ended tragically was of particular interest at the time. The magnitude of the loss—two ships and 129 men—and the mystery surrounding the fate of the crew prompted multiple expeditions to find out what happened to them.

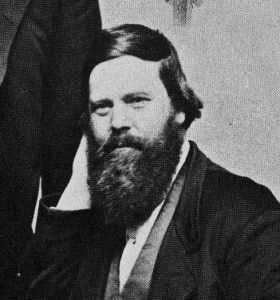

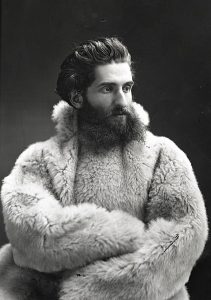

A man called Charles Francis Hall would lead two trips to the Arctic during the 1860s. He was described as a deeply eccentric man, and perhaps the unlikeliest fellow to ever become an Arctic explorer. Hall, an engraver and publisher in Cincinnati, Ohio, led a peaceful life as a family man with only a few years of formal education. However, his fascination in Franklin’s misguided expedition gave way to an obsession with the Arctic and a personal desire to discover survivors.

Even though he didn’t find survivors, he spent nearly eight years living among the Inuit people, documenting their culture more thoroughly than anybody before him.

After he arrived back in Washington, D.C., in 1869, Hall had his sights set on reaching the North Pole, after the Northwest Passage had been superseded as the main objective of Arctic explorers. Many others thought the channel could never be a profitable commercial waterway in addition to the costs of uncovering it. Hall fought hard to get President Ulysses S. Grant to support his expedition.

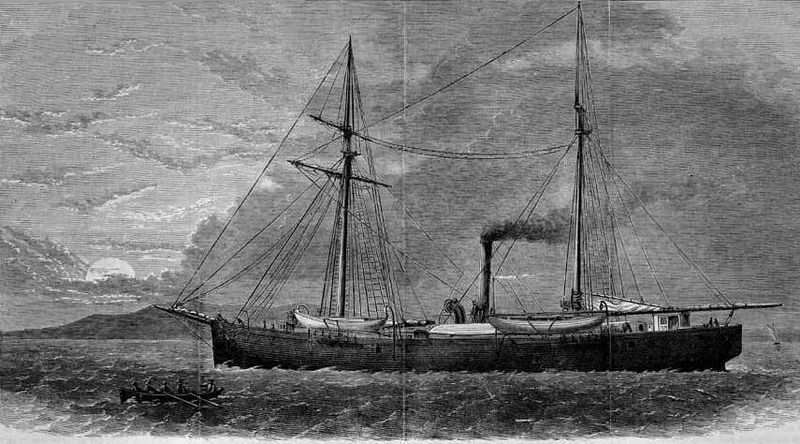

The trip received $50,000 in funding from Congress, making it the first Arctic exploration that was wholly supported by the federal government of the United States. A steamer that was utilized by the Union side during the Civil War was modified for usage in Arctic ice. On June 29, 1871, the vessel, now known as the U.S.S. Polaris, sailed from New York with 25 crew members, including Inuit guides Ipirvik and his wife Taqulittuq and their young son. Hans Hendrick, an Inuk hunter and guide, and his family joined the crew in Greenland.

A complex situation on U.S.S. Polaris

Hall was capable of surviving in the Arctic, but he was unable to manage a full-fledged mission. He was a captain without any prior navigating expertise and a commander without any military or naval rank. Sidney O. Budington served as the navigator in the end, with George E. Tyson serving as his assistant. The command of the ship was divided into three parts.

Soon after arriving on board, a German scientific team led by surgeon and scientist Emil Bessels became another cause of conflict. He had just received his medical degree from the University of Heidelberg at the age of 24. The uneducated Hall was not well-respected by Bessels and the Germans.

Tension and disagreements were intensifying after a month of sailing. Some members of the party looked destined to act in opposition anyway, so if Hall wanted something done, that’s exactly what they wouldn’t do. At least two parties were aboard, if not three.

A murder?

The Polaris progressed in the meantime, becoming the first ship in history to travel that far north when it arrived at latitude 82° 29′ N. The ship would only travel as far as that, though. The Polaris made its winter home in northwest Greenland, a location Hall called “Thank God Harbour,” roughly 500 miles south of the pole after being turned back by ice in the Lincoln Sea.

Hall returned from a two-week sledge trip to the north on October 24, 1871. After consuming a cup of coffee, he had a violent illness, including hallucinations and partial paralysis. Bessels determined that he had apoplexy (a stroke).

Hall insisted that Bessels was attempting to poison him in the meantime. Even during the period from October 29 to November 4 when his condition improved, he forbade the doctor from seeing him in bed. Hall then permitted Bessels to continue receiving treatment. On November 8, 1871, he collapsed and passed away after appearing to be better and even going for a walk on the deck. He was buried close by.

The aftermath

As the ship’s commander, Budington considered reaching the North Pole to be “a damned fool’s errand” and had no interest in doing so. On August 12, 1872, the ship departed for the south once the ice broke up. Budington gave the order to toss cargo onto the ice to buoy the ship when Polaris ran aground on an iceberg two months later.

Tyson and all of the Inuit were among the 19 members of the expedition who were on the neighboring ice pack that night when it abruptly burst. They were left trapped on the floe when the ship broke away in the dead of night. The party on the floe and the ship, which had 14 crew members (including Budington), soon lost touch. The group was rescued from the floe by a whaler off the coast of Labrador after being abandoned at sea for more than six months. They would not have survived if it weren’t for the Inuit members of the group who hunted from the edge of the floe.

The 14 survivors on the Polaris underwent their own adventure in the meantime. Budington made the decision to drive the ship aground close to Etah, Greenland, since coal supplies were running short. The local Inuit helped the group make a shelter there so they could survive the winter. The team then used wood from the Polaris to construct two boats, which they traveled south in. On June 23, 1873, a whaler off Cape York saved them.

So, who killed Charles Francis Hall?

Charles Francis Hall’s death was investigated by the Navy, but no charges were brought because of contradicting testimony and the lack of a body for an autopsy. It is obvious that there was no motivation to add scandal to a catastrophic conclusion.

Chauncey C. Loom, an Arctic historian, explored the mystery over a century after Hall’s passing and had Hall’s body exhumed in 1968. He had received significant amounts of arsenic in the two weeks before his death, according to an analysis. At the time, arsenic was frequently found in medical kits but was never administered in such large doses. Budington, who dreaded traveling up north, was a potential suspect in Loomis’ eyes. However, the arsenic had been given to induce apoplexy, which Budington would not be able to do.

Despite the lack of clear motivation, Loomis came to the conclusion that Bessels was the only person with the ability to kill Hall. Bessels publicly belittled Hall, who in turn referred to him as “the little German dancing master.” However, Loomis believed that a murderous purpose based on personal dislike was insufficient.

Another piece of evidence came to light in 2015 when Professor Russell Potter of Rhode Island College discovered an envelope addressed to Miss Vinnie Ream, 24, and bearing the postmark October 23, 1871. She was a gifted artist who had been given the job of creating an Abraham Lincoln statue when she was 18 years old. Both Hall and Bessels spent time with Miss Ream in New York before boarding the Polaris.

Potter was aware that there may have been a romantic connection between her and Bessels. Hall received a bust of Lincoln from Miss Ream, which he displayed in his Polaris cabin. According to Potter, Hall’s death could have been caused by a love triangle. “The additional motive for Bessels makes the case a strong one,” said Potter, “but [in the absence of] a time machine, I don’t think it can ever be 100 percent resolved.”