How it all began?

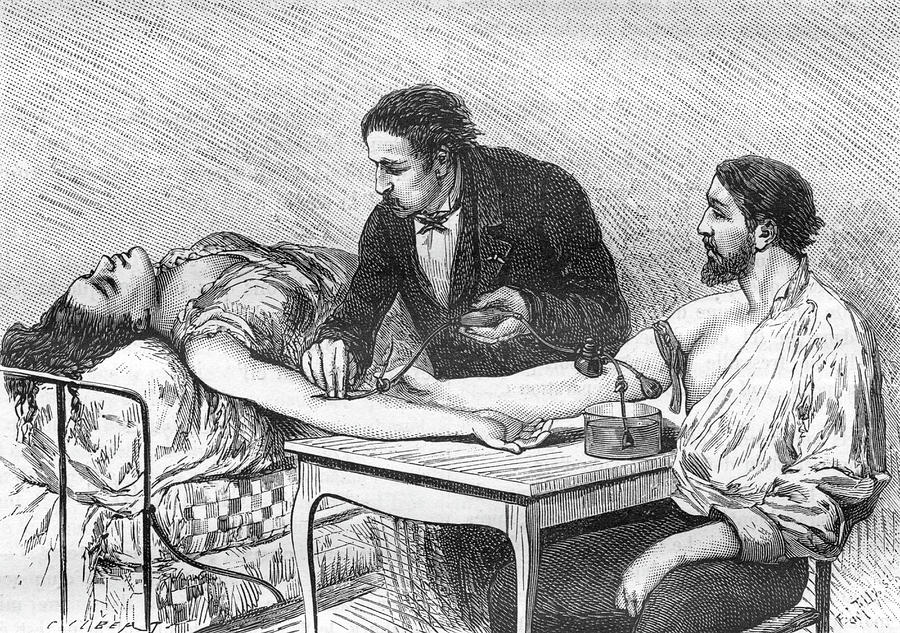

The first known experiments with human-to-human blood donation happened before humans even knew what blood types were in the early 19th century. In 1818 English doctor James Blundell proposed that a blood transfusion would be appropriate to treat severe postpartum hemorrhage. He had seen many of his patients dying in childbirth and determined to develop a remedy. Soon after, Blundell took matters into his own hands and one day he extracted four ounces of blood from the arm of the patient’s husband using a syringe, and successfully transfused it into the patient. Over the course of five years, he conducted ten documented blood transfusions, five of which were beneficial to the patients, and published these results. During his life, he also devised many instruments for the transfusion of blood, many of which are still in use today.

The discovery of blood types

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Austrian biologist, physician, and immunologist Karl Landsteiner studied blood transfusion and made some discoveries that would change everything. He found out that the blood of two people under contact agglutinates, and that this effect was due to contact of blood with blood serum. As a result, he succeeded in identifying the three blood groups A, B and O of human blood. Landsteiner also found out that blood transfusion between persons with the same blood group did not lead to the destruction of blood cells, whereas this occurred between persons of different blood groups. Based on his findings, the first successful blood transfusion was performed by Reuben Ottenberg at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York in 1907.

Later in life, Landsteiner moved to New York where together with forensic scientist Alexander Weiner, he discovered the Rhesus factor. Named after a similar property found in the Rhesus monkey, all blood has a Rhesus (Rh) factor, either positive or negative.

Both of these discoveries would become crucial to how blood transfers work today.

So What Are Blood Types?

All blood carries antigens – substances that alert the immune system to act, and each person carries a unique antigen makeup, which fall into general groups or blood types. The exact chemical composition of antigens would be discovered decades later, but Landsteiner laid down the basics.

The four major groups are decided by if they do or do not have two antigens, commonly known as A and B. Each of these antigens have an Rh factor, a positive or a negative. This leads to the commonly known blood types A+, A-, B+, B-, O+, O-, AB+, AB-.

Immunology has shown that there are over 600 types of antigens and that some people don’t even have an Rh charge.

Conclusion

Today it is well known that persons with blood group AB can accept donations of the other blood groups and that persons with blood group O-negative can donate to all other groups. Individuals with blood group AB are referred to as universal recipients and those with blood group O-negative are known as universal donors. These donor-recipient relationships arise due to the fact that type O-negative blood possesses neither antigens of blood group A nor of blood group B. Therefore, the immune systems of persons with blood group A, B or AB do not refuse the donation. Further, because persons with blood group AB do not form antibodies against either the antigens of blood group A or B, they can accept blood from persons with these blood groups, besides from persons with blood group O-negative.