In the vast expanse of the Pacific, amidst the isolation of Rapa Nui, more commonly known as Easter Island, lies a linguistic enigma that has captivated scholars and researchers for centuries. This remote, treeless volcanic island, measuring a mere 63 square miles (163 square km) and situated 2,400 miles (3,860 km) off the Pacific coast of Chile, is adorned with monolithic Moai statues, each shrouded in mystery.

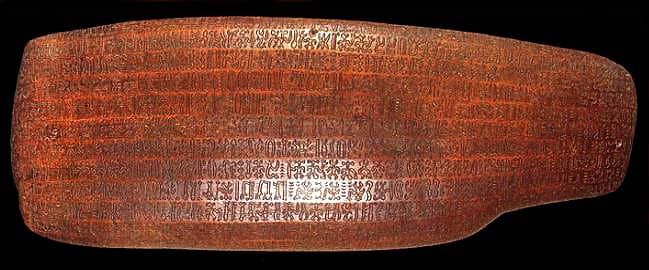

The first inhabitants arrived on Rapa Nui in the 12th century, setting the stage for a unique cultural evolution. European contact in the 1720s brought diseases that ravaged the population, followed by a devastating raid in 1863. Amidst these challenges, a missionary named Eugene Eyraud stumbled upon evidence of Rapa Nui’s written language, Rongorongo, intricately inscribed on wooden tablets in 1864. Eyraud’s observations revealed a once-abundant collection of these tablets, numbering in the hundreds within family homes. However, subsequent European visits only yielded a fraction of the original count.

Four Rongorongo tablets were sent to Rome for preservation in 1864, where they remained for over 150 years. Recent research, led by scientists from Italy and Germany, challenges the assumption that Rongorongo originated post-European contact. Radiocarbon dating of the wooden tablets revealed a surprising revelation: three tablets were crafted from trees grown in the 18th or 19th century, while the fourth tablet, dating back to the 15th century, predated European arrival on the island. This finding suggests the existence of an ancient indigenous language, possibly intentionally kept secret until the mid-19th century.

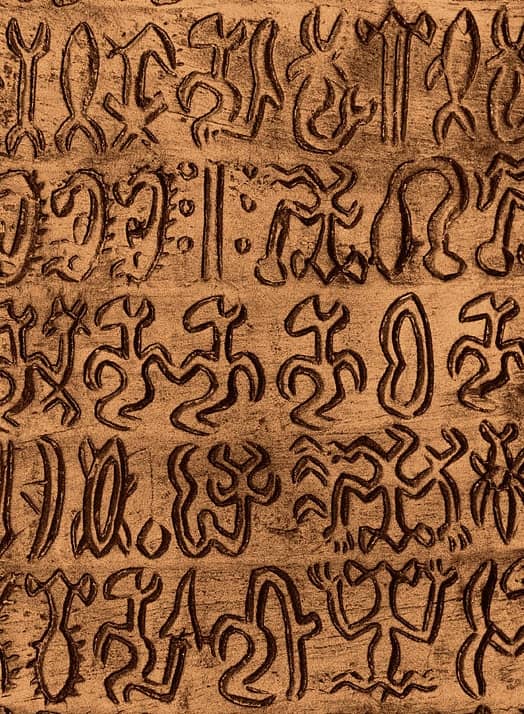

The unique characteristics of Rongorongo further complicate its unraveling. With over 15,000 pictographic characters depicting animals, plants, geometric shapes, and anthropomorphic figures, the script’s complexity remains a challenge for philologists. The script’s use, primarily by Indigenous priests, adds an additional layer of mystery, as no individuals capable of deciphering the scripts have been identified since the Peruvian invasion.

The condition of the well-preserved fourth tablet, crafted from driftwood originating in Southern Africa, hints at intentional protection, underscoring its significance to the Rapa Nui people. The debate surrounding Rongorongo’s emergence and purpose persists, with scholars grappling to classify it as proto-writing or a fully-fledged system. The script’s unique style, employing reverse boustrophedon, where every other line is upside down, adds to its perplexity.

Despite decades of research, Rongorongo remains undecipherable, shrouded in an air of mystery that continues to fascinate people. The discovery challenges preconceived notions about the origins of written language, offering a rare glimpse into the possibility of a writing system developed in isolation from external influences. If the writing system proves to be an independent invention, it would be one of very few independent inventions of writing in human history.